COctober 20E10

Obriefing

As the global financial sector recovers and moves into the post financial crisis era, there is one notion that crystallises before our eyes more acutely than ever: we need to understand systemic risk in a much more holistic way. This CEO Briefing underscores

the critical natural capital that underpins our economic activity and financial capital.

Richard Burrett Partner in Earth Capital Partners Co-Chair, UNEP Finance Initiative

In 2010, a number of large food and beverage companies, including Unilever, Nestlé,

Burger King and Kraft Foods, disengaged from the Indonesian Sinar Mas Group and its subsidiaries1 owing to the company’s alleged illegal logging. In the United States, a growing number of banks, such as Credit Suisse, Morgan Stanley, JPMorgan Chase,

Bank of America and Citibank, have increased scrutiny of lending to companies involved in mountaintop-removal mining, or have ended the lending altogether.2 BP’s oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico is another recent case that shows a growing level of materiality of biodiversity and ecosystem services (BES) issues for companies and financial institutions that provide debt, equity and insurance services.

As the world increases its awareness on the importance of nature for society, companies are seeking to operate in a sustainable way in order to protect the environment and the future of humanity. We fully support every initiative providing guidance to companies in the process of learning why biodiversity is important, and how businesses may contribute to its conservation. Knowing and understanding are fundamental

to start doing.

he links between financial services, risk and BES have, to date, been weak. Resource scarcity, loss of biodiversity and degradation of ecosystem services such as freshwater availability have, however, started to present financially material risks and opportunities for bankers, investors and insurers. This is particularly the case with financial institutions that have a large exposure or client base in industries directly dependent on BES, such as fisheries, agriculture and tourism, and industries with major BES footprints, such as the

extractive sectors.

Leading companies are taking steps to better under stand and manage their impacts and dependence on BES. Senior executives in financial institutions should recognise that biodiversity is not something to be dealt with as a peripheral issue or merely as philanthropy. Hardwiring BES into the heart of business models and core strategies is vital for longterm growth and success. This can be achieved by embedding evaluation and management of BES risks and opportunities directly in financial products and services.

This Briefing is intended for forwardlooking financial institutions to operationalise BES in the financial sector. It builds on earlier work by UNEP FI’s Bloom and Bust report3 and the TEEB reports, combined with our own analysis. This Briefing offers executives:

Insight regarding the materiality of BES for a diversified financial sector, by highlighting results from a new UNEP FI survey;

Examples of how financial insti tutions currently embed BES in lending, investment and insurance strategies and products, to enhance risk management, financial performance,

stability and future growth;

Ways in which a financial institution can competitively position itself to tap

into growing environmental markets;

Recommendations for how Chair of the Board, BCSC Bank

and a vision for how financial institutions may account for BES in 2020.

1

The evolution of environmental materiality in the financial sector

he financial crisis of 2007–2008 saw world wide financial assets fall by USD 16 trillion to

USD 178 trillion in 2008 from their peak of USD 194 trillion in 20074. Misaligned incentives, conflicts of interest, a predominance of shorttermism, failures of both accountability and responsibility and, in some cases, a misplaced sense of fiduciary duty have occurred at many different points along the investment chain and throughout the processes of financial intermediation5. In a sense, financial risk ran ahead of the world’s ability to understand and manage it.

The growth of securities, the deconstruction and (re)distribution of credit risk through securitisation, and the growth of computer power and modelling in risk management are thought to have resulted in a misplaced belief in enhanced understanding of risk6. Yet, ironically, it may have resulted in a reduced understanding of systemic risks in loan and

investment products and volatility created by the enhanced ability to trade. There is a similarity between the underlying factors that contributed to the financial crisis and the environmental risks involved. Changing environmental phenomena such as threats to biodiversity and ecosystem services (BES) loss, climate change and water scarcity, and how these translate into tangible financial risk, are also little understood in terms of financial materiality.

Financial stability may already be affected by environmental phenomena that manifest themselves through ‘slow failures and creeping risks’ in the context of ecosystem loss and degradation. Drivers are emerging

that enhance the complexity of these risks: “Increasingly,

- Increased regulatory and liability regimes by

governments seeking to protect their

ecosystems – e.g., the EU Habitats Directive;

- Increased disruptions of supply chains that rely on

wellfunctioning ecosystems such as forestry, fisheries and agriculture;

- Increased attention by media, empowerment of local populations, activism by non-governmental organisations (NGOs), and heightened sensitivity of international consumers

to environmental, social and governance

(ESG) concerns.

Figure 1 Global Risks Landscape 2010

Oil price spikes Asset price collapse

Chronic diseases

Slowing Chinese economy (<6%)

Droughts and desertification

Water scarcity

Extreme weather

loss 2010

International terrorism

- According to a World Economic Forum (WEF) survey, both ‘the severity of economic loss’ and ‘the likelihood that biodiversity has a business impact’ jumped between 2009 and 2010 (Figure 1), although the level of materiality is still perceived to be lower than

many other outside environmental and non-environmental influences8. A number of issues ranked as being of greater concern, such as coastal flooding or water scarcity, are fundamentally affected by degradation of biodiversity and ecosystem services.

Figure 2 Perception of CEOs about biodiversity

Below 1% 1-5% 5-10%

Likelihood

Africa

10-20%

45%

Above 20%

surveyed were ‘extremely’ or ‘somewhat’ concerned about biodiversity loss being a threat to business growth prospects, which varies across geographies. More executives in Latin America appear

loss as a threat to business growth prospects

Middle East

CEE

11%

Latin America

Asia Pacific

Western Europe

18%

North America

14%

36%

34%

53%

to be concerned (at 53%) than in North America (14%) or Eastern Europe (11%). See Figure 29.

A McKinsey survey10 of more than 1500 business executives revealed that 37% considered biodiversity ‘somewhat important’ and 27% ‘very or extremely important’.

2

Understanding exposure of financial institutions to biodiversity loss

oss of biodiversity and degradation of ecosystem services do not manifest themselves as systemic risks, as they do not threaten the very nature of the financial system. Increasingly, though, they are becoming financially material to bankers, investors and insurers in a myriad of other risks and opportunities. Methods to price the financial value of BES as part of a lost business opportunity or financial impact are in their infancy. However, a growing number of financial institutions, companies, governments and NGOs agree that what is needed are more sophisticated concepts and instruments to value (not simply price) how companies derive value from BES, or lose revenue. This section provides a synthesis in what ways a

diversified financial sector becomes exposed to various BES risks.

Reputational risks and emerging voluntary business principles

The Equator Principles (EPs) were initially developed in 2003 after a number of banks, including ABN Amro, Barclays, Citigroup and WestLB, received public scrutiny for their involvement in projects that damaged ecosystems11. As of June 2010, 80 banks representing 85% of the global project finance market signed up to the reinstatement of these ten principles, which means that a level playing field has started to emerge for this particular segment of the financial system. Project finance, however, only accounts for about 4% of overall global lending, arguing for a broadening of the principles beyond project finance and advisory services. Currently, the International Finance Corporation (IFC) and a few banks are assessing if and how the EPs can be extended beyond project finance12. These cases show how reputational risks related to BES and other ESG issues have transformed environmental and social due diligence in the project finance business, and potentially other financial products and services as well. The loss of natural capital (including ecosystems, biodiversity and natural resources) has direct and widespread negative effects on financial performance. Climate change and the financial crisis suggest that significant systemic risk requires coordinated policy intervention. The financial markets do not yet understand that many companies face specific risks from disruptions of vital ecosystems through their supply chains and that they need to plan for the impact of new regulation. This provides an investment

and engagement opportunity for pension funds and

other long term investors, who can encourage companies towards a better understanding and management of the risks and opportunities relating to the protection

of natural ecosystems.

Colin Melvin

CEO, Hermes Equity Ownership Services Ltd

Operational and credit risks for lenders, investors and insurers

BES has also become material for corporate and investment banking in terms of operational and credit risk. A study by the World Resources Institute (WRI) assessed financial implications of the possible restricted access of 16 oil and gas companies to reserves they own or lease in ecologically important and protected areas13. The WRI calculated that res tricted access to their reserves due to global support for conservation, and/or local opposition to oil and gas development, could lead to negative impacts on the shareholder value of these companies of up to 5%. It is questionable whether conventional risk models that are commonly used in the marketplace account for and adjust share prices for these types of risks. The BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico provides a clear – albeit extreme – example of how misinterpreted BES risks can lead to serious financial consequences for both an extractive firm and investors.

Are ESG issues leading to market and systemic risks for institutional investors that own large diversified investment portfolios?

There is one segment of the financial sector in particular where ESGrelated market and possibly also systemic risks are emerging. Institutional investors such as pension funds are longterm

investors that own a significant share of capital markets. A portfolio investor benefiting from a company externalising costs might experience a reduction in overall returns due to these externalities adversely affecting other investments in the portfolio and overall market return, through taxes, insurance premiums, inflated input prices and the physical cost of disasters17. UNEP FI and the UNbacked Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) – an initiative with over 800 signatories from the investment community that commit to six ESGfocused principles – commissioned Trucost to analyse and measure the magnitude of global environmental externalities18.

The study finds that human use of environmental goods and services caused an estimated global USD 6.6 trillion in environmental costs in 2008, taking future costs into account on a net present value basis19. This equates to 11% of the value of the global economy. If business continues as usual, this figure may rise to USD 28.5 trillion in 2050. A report titled ‘Cost of Policy Inaction’ (COPI)20 uses a different valuation approach to estimate yearly welfare loss of ecosystem services. The authors conclude that welfare loss can equate to about USD 50 billion, which could lead to a cumulative welfare loss of 7% of annual consumption by 205021.

The largest 3000 listed companies in Trucost’s database, which represent a major part of the global equity market, are responsible for USD 2.15 trillion in environmental costs in 2008. This equates to 7% of their combined revenues and about a third of their profit. Institutional investors that invest USD 100 million in a typical large, diversified equity fund could ‘own’ USD 5.6 million in external costs caused by companies held in portfolios22.

Providing clarity on ESG-related legal liability risks for investors and other financial institutions

In addition to market and operational risks, legal liability for both institutional investors and their agents is a growing issue. A UNEP FI report on the complex relationships between fiduciary law, ESG issues and institutional investment, often referred to as the ‘Freshfields Report’23, covered nine major capital market jurisdictions and concluded that ‘…integrating ESG considerations into an investment analysis so as to more reliably predict financial performance is clearly permissible and is arguably required in all jurisdictions.’ The 2009 followup report, ‘Fiduciary II’, concluded that in order to achieve the vision of the original Freshfields report, where trustees integrate ESG issues into their decisionmaking, ESG issues should be embedded in the legal contract between asset owners and asset managers, with the implementation of this framework being governed by trustees via client reporting. Equally, the report includes legal commentary that asset managers and investment consultants have a duty to proactively raise ESG issues with their clients, and that failure to do so presents ‘a very real risk that they will be sued for negligence on the ground that they failed to discharge their professional duty of care to the client…’24. The TEEB for Policy Makers report comes up with a similar message, as governments can hold companies liable for impacts on BES through the ‘polluter pays principle’25.

6 UNEP FI CEO Briefing • Demystifying materiality: hardwiring biodiversity and ecosystem services into finance To understand whether practitioners in the financial sector believe that materiality of BES is growing, UNEP FI surveyed its members in August 2010. Signatories to the PRI were also invited to respond. The intention is to understand where financial institutions see exposure of BES risks emerging for a diversified financial sector. Table 1 provides an overview of the average score for each issue. These are based on 48 responses from financial institutions, and are visualized by the colour red (‘material’), orange (‘starting to become material’) and white (‘not material’). It is interesting to see that many financial institutions see BES emerging as a material issue, particularly in banking, insurance and certain parts of the investment sector. BES is foremost becoming material in the form of reputational challenges, followed by regulatory risk, operational risk, credit risk, and legal liability. Market, liability and systemic are generally not deemed of material importance, except for the insurance sector. Systemic risk related to BES is also deemed of importance for institutional investors such as pension funds.

Table 1 Exposure of BES risks for a diversified

financial sector based on 48 financial sector practitioners

| Banking | |||||||||

| Project finance | |||||||||

| Other structured finance | |||||||||

| Corporate finance | |||||||||

| Investment | |||||||||

| Private wealth management | |||||||||

| Pension funds | |||||||||

| Insurance funds | |||||||||

| Mutual funds | |||||||||

| Sovereign wealth funds | |||||||||

| Hedge funds | |||||||||

| Private equity | |||||||||

| Insurance | |||||||||

| Insurance | |||||||||

| Reinsurance | |||||||||

Not material Starting to become material Material

Respondents were asked to fill out the table with clients from the following sectors in mind: agriculture/food and beverage, forestry, fisheries, tourism, oil and gas, mining and metals, construction/building materials, utilities (thermal and hydro).

Respondents could assign scores to each cell: 0 = not material; 1 = starting to become material; 2

= material. Scores are based on the sum in each cell divided by the number of responses. Average scores < 0.67 are considered ‘not material’ (white). Average scores between 0.67 and 1.33 are considered ‘starting to become material’ (orange). Scores > 1.33 are considered ‘material’ (red).

Demystifying materiality: hardwiring biodiversity and ecosystem services into finance • UNEP FI CEO Briefing 7

3

Evidence of biodiversity

and ecosystem services materiality

his section aims to build the business case for BES by highlighting existing evidence. The emphasis is placed on only those issues seen as material in Table 1 above, particularly reputational, operational

and legal liability risks. The questioning of BES’ economic relevance centres on its perceived ‘intangibility’. To break from this, this section reveals the ways in which BES is becoming systematically material for a significant part of the client base of banks, investors and insurers.

- Reputational risk

A McKinsey survey of executives focused on the ques tion of why biodiversity is important for businesses. It found that reputational challenges were mostly associated with biodiversity, followed by regulatory requirements (Figure 4a). Another study that focused specifically on the financial sector found similar results (Figure 4b)26.

- Operational risks

As stated before, this is especially a concern for BESdependent industries and those with major BES footprints. Here we focus on operational challenges in the following industries: oil and gas, mining, hydropower, fisheries, forestry and agribusiness.

- Oil and gas. According to research by Goldman Sachs, the average value of the world’s 230 top oil and gas projects is now USD 11.3 billion. Oil and gas companies must operate in evermore sensitive and challenging parts of the world to meet

energy needs. Nontechnical risks, including ecosystem sensitivity, can account for up to 75% of cost and schedule failures on major oil and gas projects27. Sensitive regions include, but are not limited to, (deep sea) offshore oil drilling and drilling in tropical rainforests.

The oil and gas sector has increasingly moved to deeper offshore oil drilling over the past ten years, with potentially severe repercussions on marine and coastal ecosystems. Financiers can require clients in this sector to use best-management practices to reduce failures to the highest possible extent, and refrain from financing oil and gas operations

in marine ecosystems that are deemed too fragile, and for which environmental and biodiversity safety standards cannot be met.

Oil and gas businesses also increasingly operate in biologically diverse areas such as the Amazon. There are now ~180 oil and gas blocks covering ~688 000 km2 of forest in the western Amazon, considered to be one of the most biologically diverse places on earth. Oil and gas development has caused major environmental and social impacts in

the Amazon. Given the increasing scope and magnitude of planned hydrocarbon activity, these problems are likely to intensify without improved policies28. A growing number of financial institutions refrain from financing activities in World Heritage Sites, and ‘high- conservation-value areas’. In addition, exploration within accepted international norms may be achieved by demanding from oil and gas clients the following29:

- Roadless extraction, which would greatly reduce environmental and social impacts;

- Proper attention to the rights of indigenous peoples and the outright protection of lands of peoples living in voluntary isolation, who may not be able to give informed consent.

8 UNEP FI CEO Briefing • Demystifying materiality: hardwiring biodiversity and ecosystem services into finance

Mining. Water exhibits a growing operational challenge for mining operations in regions that are either already distressed or will quickly become so. Operational risks manifest in two ways30. Water shortages can lead to power outages, especially in operations dependent on hydroelectric power to maintain operations. Second, given the high water demands of mining, companies may find that a lack of available water creates challenges in maintaining production.

Demand for water in arid and semi-arid regions in Chile could result in work stoppages or mine shutdowns if water resources become unavailable. Chile’s copper industry

is particularly affected by water scarcity concerns. A copper industry report released in 2009 projected that water consumption by the mining industry would increase by 45% by 202031. Water demand in the country – of which mining is the largest industrial component – is six times greater than water renewals32. In Chile’s arid north, mining threatens to deplete groundwater resources, which could ultimately result in the collapse of copper production – one of Chile’s chief exports33.

Hydropower. Forest and mountain ecosystems provide water to twothirds of the global population. Most businesses depend on reliable sources of water for their operations. Many businesses also influence water quality through their wastewater discharge. Given that most investments in power generation are longterm, and future water supplies are uncertain, lenders and investors are essentially increasingly placing bigger bets on adequate future water availability, and on the financial viability of their loans and investments34. A report from the World Resources Institute (WRI), for instance, showed that 79% of the new planned capacity of 60 GW will be built in areas that are already water scarce or stressed.

Fisheries. Fishing of stocks has shifted increasingly to deeper water. Expected stocks have been depleted by 90% compared to preindustrial fishing, resulting in lost economic benefits in the order of USD 50 billion annually. The real cumulative global loss of net benefits from inefficient global fisheries over the 1974 to 2007 period is estimated at USD 2.2 trillion36. According to TEEB for Business, the fishing sector is at risk of losing USD 80100 billion in income and 27 million jobs39.

- Forestry. The forestry sector is entirely dependent on natural resources, whether from natural or plantation stocks. In China, rapid deforestation has compromised ecosystem services such as watershed protection and soil conservation, leading to severe droughts or flooding in a number of major basins. Damages have been estimated at USD30 billion and thousands of lives. Elsewhere, the value of lost ecosystem services due to logging for the Chinese construction and materials sector was estimated at USD 12.2 billion annually37.

- Agribusiness. Intensified farming, overuse of chemicals and water, and overgrazing have caused the degradation of soil and agricultural land and intensified desertification, which have resulted in the loss of productive land and output, not to mention increasing water scarcity and pollution38. The TEEB for Business report (2010) mentions that, overall, about 85% of agricultural land is considered to be degraded due to erosion, salinisation, soil compression, nutrient depletion, biological degradation or pollution, while each year 12 million hectares are lost to desertification39.

Restricted supply of certain agricultural goods can cause price rises, which place pressure on food and beverage companies further down the supply chain. Additional costs from scarcity may need to be partly absorbed by companies, leading to reduced margins40. Food demand is also estimated to double by 2050, and with 70% of global freshwater withdrawals being directed to irrigation, the potential for major bottlenecks and risks for the agribusiness, food and beverage sectors remains high.

- The value of pollinators (native bees and other pollinating insects) to the global eco-

system is valued at approximately USD 190 billion a year41, through the provision of increased yields and other benefits. In the US, the 2007 collapse of bee colonies was cal- culated to have cost US producers USD 15 billion. In 2009, the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) estimated the economic impact of invasive species at USD 1.4 trillion globally; in other words, 5% GDP42.

Demystifying materiality: hardwiring biodiversity and ecosystem services into finance • UNEP FI CEO Briefing 9

Legislation and liability

The TEEB for Business (2010) report, and other recent publications, such as those by WEF and PwC (2010), provide a growing number of cases where companies are being held financially liable for BES impacts. For example, in 2003, indigenous Ecuadorians filed a suit against ChevronTexaco in an Ecuadorian court, charging the company with dumping toxic oil wastewater into 350 open pits as well as into Amazon basin wetlands and rivers that the tribes rely upon for drinking, bathing and fishing. The company is currently – in 2010 – involved in a USD27 billion court battle relating to alleged toxic contamination of local rainforests and rivers43. Financial institutions are exposed if such litigation cases affect an investee’s share price. In the case of the EU Environmental Liability Directive (ELD), financial institutions should assess if and how this enhances the exposure of clients to BES liability.

The ELD makes companies directly liable, not only for personal liability, but also for impacts on water resources, fauna, flora and natural habitats. Operators of risky or potentially risky activities can be held liable for the costs of preventing or remedying environmental damage (EU 2004)44. Under the terms of the Directive, environmental damage is defined as:

- Direct or indirect damage to the aquatic environment covered by Community water management legislation;

- Direct or indirect damage to species and natural habitats protected at Community level by the 1979 ‘Birds Directive’ or by the 1992 ‘Habitats Directive’;

- Direct or indirect contamination of the land that creates a significant risk to human health.

The new ELD is broadening the liability sphere of operations with potential adverse impacts on water bodies and biodiversity. Certain member states have chosen to implement more stringent measures; for example, by restricting the application of the ‘permit’ and ‘state of the art’ defences, expanding the range of protected species and natural habitats, or holding all operators strictly liable for biodiversity damage. Insurance firms are not obliged in most EU countries to offer coverage for this new form of ‘biodiversity’ liability, except for in Hungary, Slovenia and Sweden, where coverage by insurance companies is compulsory45.

As humankind we consider ourselves to be the predominant species on the planet. From the lens of nature, we are one of many and the most adversarial.

At YES BANK, we respect the ecosystem and our role in it. YES BANK’s Responsible Banking approach

is sensitive to environmental and social impacts as part of sustainable financing. We actively support UNEP FI in its vision for a greener world and we were the first Indian bank to become

a signatory.

Rana Kapoor

Founder/Managing Director & CEO, YES BANK

Of all species that have existed on earth 99 percent are now extinct. Let us try to do more than our best to practice and promote sustainability in all sectors in the combat against the extinction of species in order to save

the remaining one percent.

Orhan Beskok

Executive Vice President, TSKB

10 UNEP FI CEO Briefing • Demystifying materiality: hardwiring biodiversity and ecosystem services into finance

4

Making biodiversity and ecosystem services operational for finance Organisation

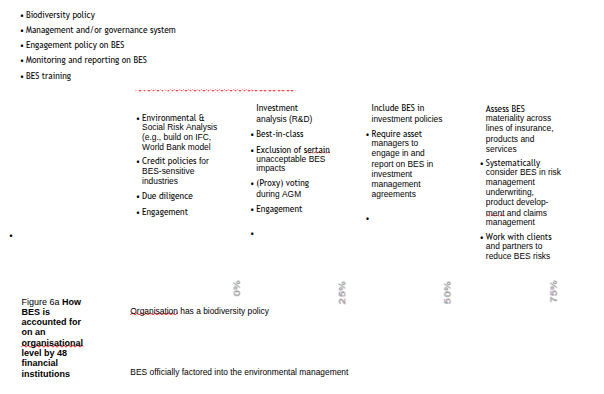

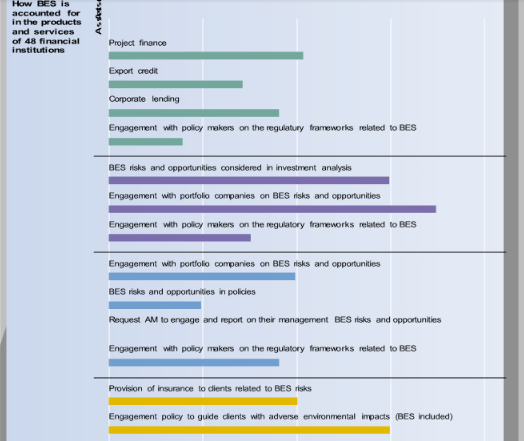

iodiversity and ecosystem services (BES) is starting to be recognized by the financial sector as a material issue, although many companies are early on in their thinking on the issue46. The diagram

below illustrates how BES can be factored into financial institutions, lending, investment and insurance.

A survey by UNEP FI asked its members how BES is currently incorporated into financial products and services, and on an organisational level. Respondents comprised representatives of 48 banks, asset managers, asset owners and insurers. Figure 6a showcases how BES is accounted for on an organisational level, whereas Figure 6b details how banks, investors and insurers deal with it in their products, services and strategies.

How Rabobank has integrated biodiversity into its core business

Rabobank is a global food and agribusiness bank. It has defined five Food & Agribusiness Principles, one Principle being ‘responsible natural resource management’. This Principle is broken down into a number of measures, such as preventing land degradation and soil erosion, minimising pollution of ground and surface water, preventing overfishing, minimising harm to sea life environment, and preserving high-conservation-value areas and biodiversity in general.

Derived from these Principles, Rabobank has defined so-called supply-chain policies for a number of sectors in which the bank is very active, specifically in food and agri- business. In each of those policies, biodiversity and ecosystem services play a central role, as they are treated as a risk or opportunity for credit decisions, acquisitions and engagement with customers. The policies focus on clients in the following sectors:

1) fisheries; 2) palm oil; 3) soy; 4) sugarcane; 5) cocoa; 6) coffee; 7) biofuels; 8) cotton;

9) forestry; 10) aquaculture; 11) oil and gas; 12) mining. Other crosscutting policies are concerned with animal welfare and genetically modified organisms. The bank is currently in the final stages of a specific policy on biodiversity.

How Credit Suisse factors in biodiversity and ecosystem services considerations

Credit Suisse addresses biodiversity in business through its high-level sustainability policy, strategy and process. Its sustainability risk management process is implemented independently but may also be fed into a broader reputational risk process. Through the sustainability risk process, the bank identifies and addresses any significant environ- mental and/or social (labour, community) impacts. However, ecosystem impacts and/ or biodiversity loss are more often than not of key concern in any given transaction, and particularly in relation to land use conversion. Credit Suisse’s process applies to all types of businesses that involve sensitive industries (e.g., extractives, forestry, agribusiness), not just loans. It has a core focus on identifying and avoiding the conversion of high- conservation-value forest, and in this regard has industry-specific sustainability policies and guidelines. The bank also encourages its clients, in any given sensitive industry, to transition towards best management practices, and requires membership in relevant industry bodies such as the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) and the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO).

How Investors Account for BES

In a large part of the investment business, BES is not considered a material risk or opportunity. The findings and recommendations of the TEEB report suggest that this situation will change, and those investors that are aware of this and act to put processes in place to understand and safeguard their investments against impact and dependence on BES are positioning themselves to realise competitive advantage. Two cases are put forward that highlight how an asset owner and an asset manager deal with BES.

Demystifying materiality: hardwiring biodiversity and ecosystem services into finance • UNEP FI CEO Briefing 13

How Insurers Account for BES

For insurance companies, BES risks can adversely impact both their underwriting profitability (e.g., floods due to deforestation leading to insured or uninsured losses) and investment returns. Insurance companies are not only risk carriers that provide insurance products – they are also risk managers through their loss prevention and loss mitigation services. Opportunities arise for forwardlooking insurers to develop new products that can differentiate themselves from competitors. HSBC Insurance in Brazil and Tokio Marine & Nichido Fire Insurance in Japan have developed new insurance products. They compensate for the carbon emissions of clients by conserving native forests (in the case of Brazil) and planting mangroves (in the case of Japan).

With their long maturation, forests are a suitable asset to match with commitments by pension funds to longterm income streams. Products like weather derivatives and catastrophe bonds can provide investors with risk transfer solutions.47 The insurance industry, understandably, is quite cautious in developing new products, particularly for ‘emerging risks’, including environmental risks such as BES. Nevertheless, there are good indicators of opportunities. For example, data from a 2009 global survey by the UNEP FI Insurance Working Group on understanding and integrating ESG factors in insurance underwriting and product development suggest that biodiversity loss and ecosystem degradation and water management combined present opportunities across agroforestry, casualty, health, life, marine aviation and transport, and property48.

14 UNEP FI CEO Briefing • Demystifying materiality: hardwiring biodiversity and ecosystem services into finance

5

Bearish or bullish? Tapping into growing environmental markets

Financial institutions can seize opportunities related to BES in different ways:

- Early movers that can demonstrate integration of BES can bolster their organisation’s reputation and create value for marketing practices.

- Building capacity inhouse on BES can be beneficial in terms of advisory services for corporate clients.

- Advising clients how to integrate BES in supply chain management can lead to cost reductions for clients.

- Environmental markets are increasingly starting to take shape in a growing number of countries (Table 2). Financial institutions that understand these markets may profit through offering brokerage services, registries, or specialised funds.

A number of countries have pledged a combined amount of USD 5.8 billion49 to get markets started for carbon credits related to avoiding deforestation (REDD+). Estimating the future size of a REDD+ market

Table 2 Environmental markets that factor in BES directly or indirectly

is challenging, as it depends on factors such as future emission trends in countries, stringency of targets in a new post2012 climate change agreement and the performance of ‘competing’ mechanisms. Rough estimates can be made on the supply side. A study by EcoSecurities in 200750 calculated annual market sizes for REDD+ credits between USD 3 and 30 billion, for reduction targets in deforestation of between 5% and 50% compared to a 1990–2005 baseline.

| BES asset class | Market value | Year | Market type |

| USD 1.8 – 2.9 billion | 2008 | Private (cap and trade)51 | |

| Biocarbon Voluntary OTC (forestry carbon), incl. REDD+ Chicago Climate Exchange – forest carbon CDM – reforestation / afforestation | USD 31.5 million USD 5.3 million USD 0.3 million | 2008 2008 2008 | Private (voluntary)52 Private (voluntary) Private (cap and trade) |

| Cosmetics/ personal care / pharmaceuticals: bio-prospecting contracts | USD 30 million | 2008 | Private (voluntary)39 |

| Certified agricultural products, incl. non-timber forest products (NTFPs) | USD 40 billion | 2008 | Private (voluntary)39 |

| Certified forest products (FSC, PEFC) | USD 5 billion (FSC certified products) | 2008 | |

| Payments for Watershed Services (private voluntary) | USD 5 million (e.g. Costa Rica, Ecuador) | ||

| Payments water-related ecosystem services (government) | USD 5.2 billion | 2008 | Public39 |

| Other payments for ecosystem services (government-supported) | USD 3 billion | 2008 | Public39 |

| Private land trusts, conservation easements (e.g. North America, Australia) | USD 8 billion (in the U.S. alone) | 2008 | Public39 |

Recent years have also witnessed a number of attempts to set up investment funds that invest in businesses and projects that render both ecological and financial returns, although fund sizes are notably limited. Early attempts have been predominantly started by NGOs such as Conservation International through Verde Ventures, and The Nature Conservancy through the EcoEnterprise Fund. The latter invested USD 6.3 million of debt capital in 23 small and medium enterprises. More recently, a number of companies have entered the scene with innovative investment approaches that seek to make larger investments. Three cases are shown here: Sumitomo Trust’s new Biodiversity Investment Fund; AgroEcological’s innovative investment approach to organic agriculture; and New Forests’ investments in environmental markets. Such funds may provide interesting alternatives for investment managers and owners seeking an avenue to underdeveloped and novel markets.

Demystifying materiality: hardwiring biodiversity and ecosystem services into finance • UNEP FI CEO Briefing 15

16 UNEP FI CEO Briefing • Demystifying materiality: hardwiring biodiversity and ecosystem services into finance

6

A Vision for 2020

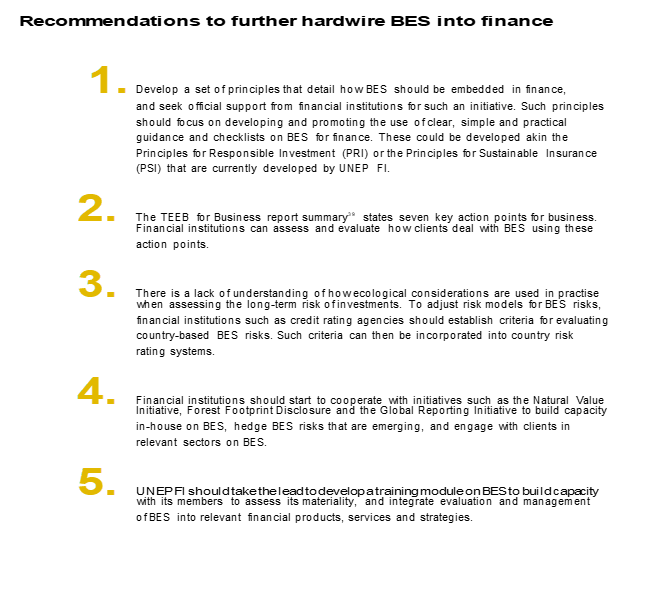

e cannot look into a crystal ball to picture what 2020 will look like. However, it is plausible that biological diversity and the ecosystem services that underpin it will further decline. Successful and responsible finance means being able to understand how macro and micro external factors like climate change, ecosystem degradation and water scarcity affect consumer behaviour, demand for products, and the competitiveness of sectors and companies in different geographies. Governments may increasingly step up to protect ecosystems in order to make significant contributions to halt biodiversity loss by 2020. This will further amplify the legal liability of firms with severe negative impacts on ecosystems. Lenders, investors and insurers need to properly value this new form of liability in the creditworthiness of a client. With the Rio+20 Earth Summit in 2012 approaching, this section seeks to provide a vision for 2020 of the implications for banks, investors and insurers. It also provides recommendations for how to further

hardwire BES into financial products and services.

For banks

- The legal liability of corporate clients in sectors with severe negative impacts on BES is further amplified. As a result, BES is integrated into routine risk analyses and management systems.

- Consumers will increasingly understand the links between finance, corporate activities on the ground and ecosystem degradation, and demand from their banks that certain types of finance with unacceptable social and environmental impacts be banned.

- Mismanagement of impacts and dependence on BES will become increasingly significant reputational risks by association for banks, especially in relation to structured finance.

- Opportunities for new products and services are arising that positively influence BES, and can offer a return.

For investors

- Investors realise that a growing number of companies in the highlyBES dependent sectors, such as fisheries, tourism, forestry and agriculture, will become less competitive due to an adverse ecological state of the commodities they depend on. At the same time, companies in an increasing number of extractive, industrial and commercial sectors behave more progressively as they understand that longterm shareholder value is enhanced by both embedding ESG considerations into their longterm strategy and by fully disclosing their progress to investors. Investors stimulate this process by increasingly becoming active owners through engagement and voting.

- BES is recognized as a financially material factor that influences the economics and stock value evaluation of sectors, similar to what we see today with climate change or carbon footprints.

- Mainstream investors expect that investee companies have implemented a strategic approach to addressing their impacts and dependencies on biodiversity and ecosystem services, and that they will disclose this approach in their annual reporting.

- Investors will actively search for investments that provide solutions to BES challenges in much the same way that investors are funding investments providing solutions to climate change challenges today. Institutional investors will routinely include consideration of BES risks/opportunities when searching for new fund managers.

For insurers

- Governments are stepping up to protect ecosystems in order to make significant contributions to halt biodiversity loss by 2020. This will further amplify the legal liability of firms with severe negative impacts on ecosystems.

- The development of prudential legal frameworks on BES risks will underpin the insurability of BES risks, the development of relevant insurance products, and the management of insurance claims.

Demystifying materiality: hardwiring biodiversity and ecosystem services into finance • UNEP FI CEO Briefing 17

This study is an essential step forward in recognising the value of all living organisms and ecosystems for our own well being. This being the year of biodiversity, the business community should publicly embrace its responsibility to protect and restore ecosystem services.

ASN Bank, for one, has published its Issue paper on Biodiversity, formulating its investment policy on

biodiversity. The UNEP FI CEO Briefings continue to provide guidance to ASN Bank in formulating and implementing this policy. ASN Bank hopes it will do the same for other financial institutions.

Ewoud Goudswaard

Managing Director, ASN Bank

18 UNEP FI CEO Briefing • Demystifying materiality: hardwiring biodiversity and ecosystem services into finance

Notes and references

1. Unilever takes stance against deforestation. www.unilever.com/sustainability/news/news/

december2009unilevertakesstanceagainstdeforestation.aspx.

Nestle: SpeechesAndStatements/AllSpeechesAndStatements/statement_ Palm_oil.htm?wordId=D7E0005DF7D94AD385D7AA631CBA0E8E

Burger King to stop buying oil from Sinar Mas. http://baliholidayinfo. com/content/burgerkingstopbuyingoilsinarmas. Krafting a new story on oil palm: http://understory.ran.org/2010/08/19/kraftinganew storyonpalmoil/

2. New York Times, 2010. Banks Grow Wary of Environmental Risks. 30 August 2010. www.nytimes.com/2010/08/31/business/energy environment/31coal.html?_r=3

3. UNEP FI, 2008. Bloom or Bust? UNEP Finance Initiative: Geneva UNEP FI, 2007. CEO Briefing – Bloom or Bust? UNEP Finance Initiative: Geneva

4. McKinsey, 2009. Global capital markets: Entering a new era. McKinsey Global Institute

5. UNEP FI, forthcoming. Lenses and clocks – Financial stability and systemic risk. UNEP Finance Initiative: Geneva.

6. The Economist, 2010. The Gods Strike Back. A special report about financial risk. February, 2010.

7. Mulder, I., 2007. Biodiversity, the Next Challenge for Financial Institutions? World Conservation Union (IUCN): Gland

8. WEF, 2010. Global Risks 2010 report. World Economic Forum: Geneva

9. PwC. 2010. PricewaterhouseCoopers 13th Annual Global CEO Survey 2010. London

10. McKinsey, 2010. The next environmental issue for business: McKinsey Global Survey results. McKinsey Quarterly.

11. Equator Principles, 2006. A financial industry benchmark for determining, assessing and managing social and environmental risk in project financing. www.equatorprinciples.com

Esty, B. C., Knoop, C., and Sesia, A., 2005. The Equator Principles: An industry approach to managing environmental and social risks. Harvard Business School, Boston

12. Facilitated by the IFC, a small group of financial institutions is looking into whether and how the Equator Principles can be expanded beyond project finance.

13. Austin, D., and A. Sauer, 2002. Changing Oil: Emerging environmental risks and shareholder value in the oil and gas industry. World Resources Institute: Washington, D.C.

14. “Low carbon growth in Asia”, comments on BP at the 16June, 2010, UNEP FI event in Seoul, Republic of Korea, by Michael Dieschbourg, CEO, Legg Mason Global Currents

15. Bloomberg, 2010. BP’s Credit Rating Cut by Fitch to Two Levels Above Junk. www.bloomberg.com/news/20100615/bpscreditrating cutbyfitchtobbbtwolevelsabovejunkfromaa.html (consulted August 2010)

16. Bloomberg, 2010. Insurers Raise DeepWater Oil Rig Prices 50% After BP Spill, Moody’s Says. www.bloomberg.com/news/20100603/ insurersraisedeepwateroilrigprices50afterbpspillmoodyssays. html (consulted August 2010)

17. Seitchik, A., 2007. CFA, Climate Change from the Investor’s Perspective.

18. PRI and UNEP FI, forthcoming. Universal Ownership: Why externalities matter to institutional investors.

19. The actual value of externalities is likely to be higher, since the analysis excludes most natural resources used, as well as environmental impacts such as water pollution, due to lack of global data. The COPI (Cost of Policy Inaction) used a different approach. Due to lack of global data, the TEEB analysis excludes the majority of natural resources

used, as well as environmental impacts including water pollution, land use change, soil degradation, pesticide and fertiliser residues and

emissions of ozonedepleting substances. Taken from “PRI and UNEP FI, forthcoming in 2010. Taking the environment into account. Universal Ownership: Why externalities matter to institutional investors”

20. Braat, L., and P. ten Brink, 2008. Cost of Policy Inaction (COPI): The Case of not Meeting the 2010 Biodiversity Target. European Commission: Brussels

21. TEEB, 2008. The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity An interim report. European Commission, Brussels

22. This is based on Trucost’s analysis of externalities from 2,439 companies listed in the Index MSCI All Country World Index, used as a proxy for a hypothetical equity portfolio that reflects Index sector weightings. Taken from “PRI and UNEP FI, forthcoming. Universal Ownership: Why externalities matter to institutional investors”

23. Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer and UNEP FI, 2005. A legal framework for the integration of environmental, social and governance issues into institutional investment. UNEP FI: Geneva

24. UNEP FI, 2009. Fiduciary responsibility – Legal and practical aspects of integrating environmental, social and governance issues into institutional investment. UNEP FI: Geneva

25. TEEB, 2009. The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity for National and International Policy Makers – Summary: Responding to the Value of Nature 2009. European Commission: Brussels

26. Mulder, I. and T. Koellner, in press. Hardwiring Green – How Banks Account for Biodiversity Risks and Opportunities. Journal of Sustainable Finance and Investment

27. Snashall, D., 2010. Keeping oil and gas mega projects moving – grappling with Non Technical Risk. Environmental Risk Management

– ERM.www.erm.com/AnalysisandInsight/Articles/Keepingoilandgas megaprojectsmovinggrapplingwithNonTechnicalRisk/ (consulted August 2010)

28. Finer M, Jenkins C.N, Pimm SL, Keane B, and C. Ross, 2008. Oil and Gas Projects in the Western Amazon: Threats to Wilderness, Biodiversity, and Indigenous Peoples. PLoS ONE 3(8): e2932. doi:10.1371/journal. pone.0002932

29. Finer M, Jenkins C.N, Pimm S.L, Keane, and B, Ross C, 2008. Oil and Gas Projects in the Western Amazon: Threats to Wilderness, Biodiversity, and Indigenous Peoples. PLoS ONE 3(8): e2932. doi:10.1371/journal. pone.0002932

30. Miranda, M., and A. Sauer, 2010. Watered Down? Water Risks and Disclosure in the Mining Sector. World Resources Institute: Washington D.C.

31. Cochilco, 2009. “Consumption of water in the Chilean mining industry: actual situation and projections.” Presented November, 18 2009.

32. www.geim.org/archivos/session_d/Natural%20Water%20Resources. ppt#312,34,Slide 34

33. Global Water Intelligence. 2009. A new dawn for desalination in Chile. Global Water Intelligence. Vol. 10(12). Available at: www.

globalwaterintel.com/archive/10/12/general/anewdawnfordesalination inchile.html.

34. UNEP FI, 2010. Chief Liquidity Series issue 2 – Power Sector. UNEP FI: Geneva

35. Sauer, A., Klop, K., and M. Agrawal, 2010. Over heating Financial Risks from Water Constraints on Power Generation in Asia. World Resources Institute: Washington D.C.

36. World Bank and FAO, 2008. The Sunken Billions: Economic Justification for Fisheries Reform. World Bank: Washington D.C.; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome

37. McVittie, 2010 in TEEB, 2010. Business impacts and dependence on biodiversity and ecosystem services, in The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity: TEEB for Business

38. WEF, PwC, 2010. Biodiversity and Business Risk: A Global Risks Network Briefing. World Economic Forum: Geneva

39. TEEB, 2010. The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity Report for Business Executive Summary. European Commission: Brussels

40. F&C Management, 2004. Is biodiversity a material risk for companies? An assessment of the exposure of FTSE sectors to biodiversity risk. F&C Investments: London

41. Operation pollinator. www.operationpollinator.com/need.asp

42. CBD Business and Biodiversity newsletter. www.cbd.int/doc/ newsletters/newsbiz200906en.pdf http://www.cbd.int/doc/newsletters/ newsbiz200906en.pdf

43. The Sunday Times Magazine, The Amazon’s Dirty War, November 209.

44. http://europa.eu/legislation_summaries/enterprise/interaction_ with_other_policies/l28120_en.htm

45. MMC, 2009. New environmental liabilities for EU companies. Marsh Ltd: London

46. Mulder, I. and T. Koellner, submitted. Hardwiring Green – How Banks Account for Biodiversity Risks and Opportunities. Journal of Sustainable Finance and Investment.

47. UNEP FI, 2007. Insuring for sustainability Why and how the leaders are doing it. UNEP FI, Geneva.

48. UNEP FI, 2009. The global state of sustainable insurance – Understanding and integrating environmental, social and governance factors in insurance. UNEP FI Insurance Working Group: Geneva

49. UNEP, 2010. Bringing forest carbon projects to the market. United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi

50. EcoSecurities, 2007. REDD Policy Scenarios and Carbon Markets A policy brief. Oxford.

51. Madsen, B., Carroll, N., Moore Brands, K., 2010. State of Biodiversity Markets Report: Offset and Compensation Programs Worldwide. Ecosystem Marketplace: Washington D.C.

52. Hamilton, K., Chokkalingam, U., and M. Bendana, 2009. State of Forest Carbon Markets – Taking Root and Branching Out. Ecosystem Marketplace: Washington D.C.