Introduction

Corporate boards across the globe are wrestling with an increasingly complex array of critical issues. In recent years, sustainability has taken center stage. But pressing new matters—notably the rapid rise of generative AI (Ge- nAI) and intensifying trade and geopolitical disruptions— have also become prominent on the agenda.

For boards in emerging markets, however, these challenges are compounded by their companies’ unique circumstanc- es: still-evolving governance practices, a higher share of ownership with a controlling interest (which comes with its own set of challenges and opportunities), and the realities of their operating environment, including a more nascent regulatory landscape.

How can boards in emerging markets more effectively navigate these challenges? This was a core question we probed for the latest edition of our report, part of a series produced jointly with Heidrick & Struggles and INSEAD, on how boards are responding to today’s complex trends and disruptions. In addition to a global survey, this year’s study included multiple roundtables for board members and executives held throughout the world.

Here, we present key findings and insights on emerging markets boards, highlighting the differences in attitudes and practices between them and boards throughout the rest of the world. We explore the unique characteristics and challenges of corporate governance in these regions and examine how the state of governance influences boards’ ability to navigate complexity. Building on these insights, we conclude with a set of detailed questions that will help boards and management assess their current capability level and cultivate the best practices critically needed to manage sustainability and the complex array of other challenges they face.

Boards in Emerging Markets Face a Dual Set of Challenges

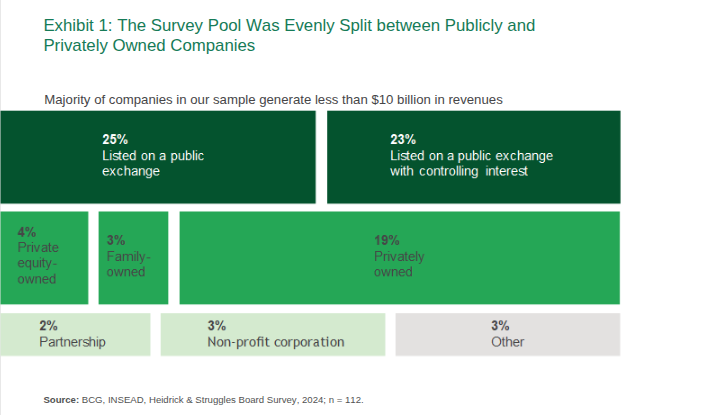

First, some context: of the 112 emerging markets board members who participated in our survey, 62% have over five years of experience as directors, and 18% are currently CEOs. They come from diverse industries, including bank- ing and finance (19% of respondents) and manufacturing (26%). They also represent businesses of various sizes and structures; for instance, 48%, nearly the same percentage as the global sample, serve on the boards of publicly trad- ed companies. However, a larger share (23%) serve on a listed company with controlling interest (compared to 12%

in our global sample). (See Exhibit 1.) To capture more detailed insights, we also conducted six roundtables involv- ing more than 70 directors in Kuala Lumpur, Jakarta, São Paulo, Nairobi, Baku, and Istanbul. (For more on the study, see the sidebar “About Our Report.”)

Through both our survey and roundtables, we learned that boards in emerging markets confront two main sets of challenges. When it comes to integrating sustainability into the core of their businesses, the obstacles they face strongly resemble those their developed market counter- parts face. But the context in which they must address these challenges is markedly different. By “context,” we mean more than just their internal governance and oper- ating realities.

“Context” also encompasses the broader governance landscape, which, in many emerging markets, is still evolv- ing, both in terms of best practices and institutional frame- works (including legislative and regulatory structures), as well as political realities. These factors further complicate the process of accounting for other external factors in business strategies, such as GenAI, trade,

and geopolitical issues.

How Emerging Markets Boards Are Managing Sustainability

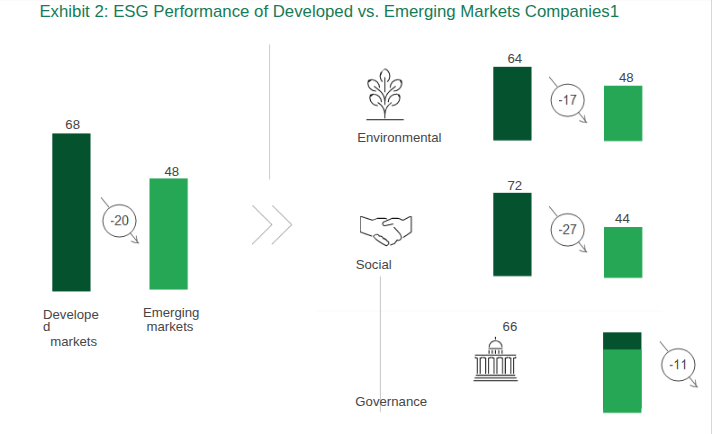

There is a significant gap in sustainability progress be- tween developed market companies and those in emerg- ing markets, according to the most recent available data from The World Bank and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. On a weighted basis, developed market companies scored an average of 68 in

environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance versus a score of 48 for emerging markets companies. (See Exhibit 2.) Deeper analysis revealed that emerging mar- kets companies exhibit lower maturity across all ESG pillars, with the “social” pillar having the biggest gap.

Two main factors underlie this disparity. Despite having similar challenges, developed market companies generally embarked on their sustainability journey much earlier— whether driven by societal pressures or regulatory or legis- lative mandates—which thus gave them more time to make progress. Their earlier start also means they had the benefit of abundant access to ESG expertise, whereas such access remains limited in emerging markets.

The performance gap is also a function of more funda- mental structural differences. Companies in emerging markets often follow the sustainability frameworks and

legislation created in developed economies, which may not fully reflect their local circumstances. As a director from a Brazilian investment firm noted:

“We talk about bridging the ESG gap between emerging and developed markets as if the developed markets have all the answers. We [need to] bring our own challenges to the table.”

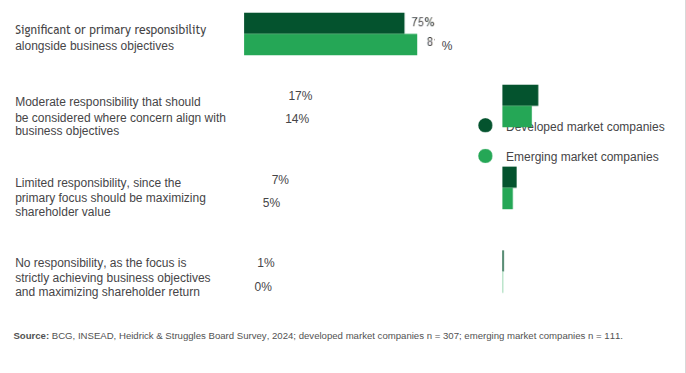

Exhibit 3: Emerging Markets Companies Put Slightly More Responsibility on the Board to Address Broader Societal Concerns

When asked to describe board responsibility for addressing broader societal concerns, respondents cite it as a…

Minimal Differences in Internal Challenges and Approach…

Overall, we found few substantial differences between emerging markets boards and boards in the global sample in how they approach the challenges of sustainability. Both groups regard the commitment to sustainability as essen- tial; in fact, fewer emerging market respondents (19%) considered it a “nice to have” than the developed market sample (24%). Both emphasize the need to strengthen their companies’ risk management and horizon-scanning capabilities. And both promote stakeholder engagement and advocate adopting more flexible long-term resource allocation strategies.

We did, however, uncover some material differences—dif- ferences we believe are rooted in more general corporate governance challenges, as we describe later.

Boards in emerging markets spend less time on sustain- ability education (29%) than the global average (49%).

Importantly, though, emerging markets boards recognize the need to access critical sustainability information. And they tend to rely more on partnerships with external orga- nizations to achieve this (31%, versus 22% in developed markets).

Our roundtable discussions revealed that with emerging markets boards, sustainability is more often treated as a separate agenda item than as an element integral to the company’s overall strategy. As a result, it can be harder to articulate the business case for sustainability and demon- strate its role in driving long-term value.

As one Azerbaijani roundtable participant noted, sustain- ability is rarely the primary driver for action. However, when there is a strong business case, sustainability can become an added incentive.

“There are massive uncertainties regarding returns, particularly in the short and intermediate terms,”

explained a director who serves on the board of a South- east Asia mining company. In addition, the rise of the chief sustainability officer (CSO)—a role that has gained greater visibility in developed market companies, and one that now typically reports directly to top leadership—signifi- cantly helps prioritize sustainability. In most emerging markets, however, it’s not yet common practice for the CSO to be positioned at a senior enough level to influence strategic decisions effectively.

…But Significant Differences in Operating Context

One of the most striking differences in operating context is the disproportionate impact of climate change on develop- ing nations. Yet companies in these regions are governed by sustainability targets set by developed economies. As a director from the financial industry in Brazil (a former government official) noted,

climate is doing to the Amazon. Right now, the Rio Negro at Manaus has dried up completely, disrupting connectivity between cities and impacting supply chains.”

Beyond the disparate climate impacts are differences in institutions and market structures that further inhibit progress on sustainability, such as:

Limited access to green finance and other financing constraints. Companies in emerging markets struggle to find funding sources for sustainability initiatives. Develop- ing regions face a funding gap for energy transition initia- tives that is twice as large as that of their developed region counterparts. One reason is taxonomy: according to a 2024 World Bank report, only 10% of emerging markets have adopted green and sustainable taxonomies compared to 76% in advanced economies. These taxonomies define and classify investments and activities that support climate targets and are crucial for increasing climate-related lend- ing. Their slow adoption in emerging markets has limited the available avenues for sustainable finance.

The impact of ESG-linked financing instruments remains modest. As one director from Istanbul pointed out “The 1% to 2% difference [from commercial loan rates] isn’t particularly attractive.” The obstacles to financing not only slow progress, but also exacerbate the difficulties of meet- ing local and international sustainability goals. Emerging markets companies can’t develop at the same scale as their developed market counterparts. These financial constraints put additional pressure on boards to find alter- nate ways to address sustainability challenges while main- taining their companies’ competitiveness.

Different sources of influence. In developed markets we have seen that employees (both existing and prospective) have had a lot to do with driving initial corporate sustain- ability efforts. In contrast, as a roundtable participant from Azerbaijan pointed out, regulators and investors typically provide the first push in emerging markets. However, he

added, companies in these markets anticipate that sus- tainability will become increasingly important for attract- ing talent in the coming years.

A Web of different regulations. Emerging market com- panies that supply developed markets face an ever-ex- panding set of regulations that vary from region to region. Noted one director from an Southeast Asian-based compa- ny that supplies raw materials for consumer products,

“We do everything the world asks of us, but as soon as we comply with all the rules, they move the goalposts again.”

Moreover, many emerging market boards underestimate the impact of international regulations, such as the Euro- pean Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) and the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CS3D), on their operations. Many of these regulations apply not only to companies based in the EU, but they also have ripple effects down the supply chain, directly affecting suppliers, regardless of their location. Either emerging markets companies underestimate the potential impact or are adopting a “wait and see” posture, which could leave them at a competitive disadvantage, especially as the regu- latory landscape evolves. As a director from a Malaysian food and beverage company observed,

“Complying early with the new regulations is a competitive advantage.”

Emerging Markets and their Governance Realities

The progress that emerging market boards are making in integrating sustainability into their oversight is often hin- dered by general corporate governance practices, which are not adapted to handle the kind of complex challenges companies face today, as many directors have observed. This not only complicates the integration of sustainability into governance structures, but it also makes it difficult to grasp how other emerging trends—such as GenAI, trade dynamics, and geopolitical risks—will impact how compa- nies create value, and to what extent.

Adding to the challenges of governance maturity are the gaps in institutional frameworks and legislative and regu- latory structures, along with political realities that make it hard for the board to provide the comprehensive oversight necessary to sustain and grow the value of the business. This leaves companies with little external support or pres- sure to improve their governance standards. Without the incentive of firm regulatory oversight, companies are left to drive governance improvements on their own. This can potentially lead to a patchwork of varied approaches, as each board sets its own internal priorities rather than aligning with cohesive external standards.

Board members and executives in emerging markets clearly recognize the need for corporate governance re- form. A director from a South American pharmaceutical company put it succinctly:

“We need to retrofit corporate governance and board practices from the ground up. While no one enjoys the tedious details of rewriting board and committee charters or bylaws, it’s necessary [in order] to align with today’s evolving complexities.”

Among our key findings on the realities of emerging mar- ket corporate governance are the following.

Not Enough Diversity and Independence

A key area where emerging market boards are seeking improvement is in their composition and diversity. In these markets, concentrated ownership structures such as fami- ly- or state-controlled entities are prevalent. And while these structures can offer organizational stability and

long-term vision, they also mean that board diversity is often limited. Traditionally, boards in these regions rely on conventional professional profiles, so that in background, expertise, generation, and overall mindset, most are quite homogeneous. Remarking on his region, another director in Indonesia observed,

“New board nominations are still mostly done by one friend calling the other.”

Independent board members can lend diverse perspec- tives, bolstering a company’s ability to adapt and remain competitive in a rapidly changing global environment. As a family member of a Turkish family-owned conglomerate noted,

“Independent board members, especially foreign ones, really make a difference. They aren’t afraid to make difficult decisions that may affect short- term profitability but are essential for long-term value creation. They should be mandatory.”

Tradition Can Impede Reform

One of the key issues highlighted by roundtable partici- pants was the entrenched nature of some emerging mar- kets boards. Some longstanding board members are ap- pointed based more on personal connections that on interest or expertise. Such individuals tend to be more focused on preserving the status quo than on driving meaningful change. As one board member at our Nairobi roundtable put it: “Boards should start dealing with people who don’t contribute, who are silent or who don’t show up to board meetings.”

The status-quo mindset is especially evident when it comes to board education and competence development. Despite the recognition that ongoing education is vital, our data shows that board education and skills development in emerging markets are not given the priority they are given at many developed market companies.

In fact, we saw evidence of this disparity in our roundtable participation. While many board members saw these events as valuable learning opportunities, some passed off their participation to management, implying that it was not for them.

Finally, in our roundtable discussions on the relationship between boards and management, we learned that the board-management dynamic in some emerging market companies tends to be more transactional than collabora- tive. Such a relationship prevents the kind of deep, candid engagement necessary for boards to fully perform their oversight function and contribute value to management and the company. A participant at our Nairobi

roundtable noted that:

“Management is mostly asking the board for blessings; they are less interested in getting questioned.”

A Manifest Desire to Invest in the Future

Despite the challenges they face, emerging market boards are taking decisive action in response to sustainability and other global trends—in many cases, more so than their developed market counterparts. Notably, more than 60% of directors in emerging markets reported that their com- panies are making long-term investments in new sustain- ability-related technologies, compared with 48% of devel- oped market directors. Additionally, 16% of emerging market companies are pursuing mergers and acquisitions prompted by GenAI, surpassing the 10% seen in developed markets.

Regardless of the absolute monetary amount of their investments (likely smaller than in developed market companies), the decisive action of emerging markets boards highlights the growing recognition that they must move swiftly to remain competitive. Their proactive stance on other important issues such as GenAI, trade, and geo- political disruption reflects an increasing understanding of the importance of adapting to global shifts to secure long- term success.

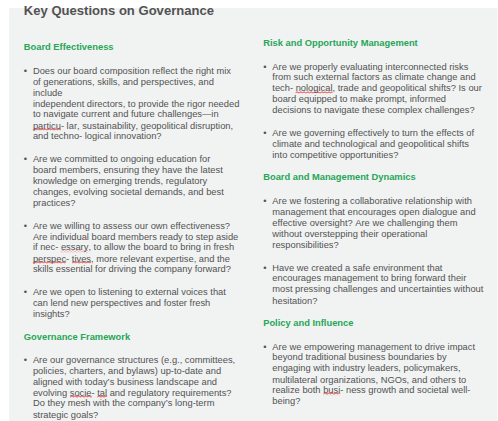

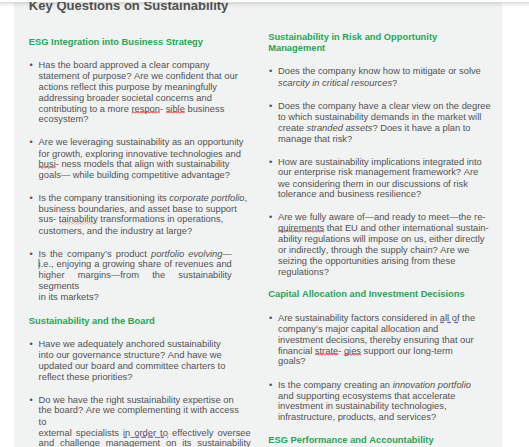

Moving Forward: Critical Questions

The business environment in emerging markets is evolving rapidly, and companies striving for long-term competitive advantage must embrace sustainability as a core part of their transformation. For any board in any market, steering a company effectively requires mastering the material sustainability issues that are shaping competitive advan- tage in its particular industry. However, as we’ve noted, the journey is more complex in emerging markets, because governance practices, the general operating environment, regulatory landscapes, and political realities are still evolv- ing, and at different rates.

Nonetheless, as demanding—or daunting—as their role is today, boards that are actively engaging in governance reform find themselves in an advantageous position. By shedding outdated practices, they can develop fresh, inno- vative approaches to tackle the considerable challenges ahead. Amid a more nascent regulatory environment, they have the opportunity to help shape governance policy and practices. Ultimately, they are well-positioned to forge a more responsible and resilient business ecosystem, driving long-term value while contributing to the development of future-forward governance frameworks.

Directors can start by addressing key questions that help evaluate both their overall governance practices and struc- tures, as well as the effectiveness of their sustainability oversight.

About the Authors

Ron Soonieus is a senior advisor to Boston Consulting Group and a director in residence at the INSEAD Corpo- rate Governance Centre. He focuses on the nexus of corpo- rate governance and corporate strategy. He is based in Amsterdam.

Burak Tansan is a managing director and senior partner at Boston Consulting Group, based in Istanbul. He is also the global topic leader for ESG in Emerging Markets at BCG, and has been advising leading conglomerates and companies in the region on sustainability, transformation, and effective corporate governance. tansan.burak@bcg.com

Marcos Aguiar is a managing director and senior partner at Boston Consulting Group, based in Brazil. He is a senior member of the firm’s Strategy, Technology, and Global Advantage practices and an expert in agenda setting and large-scale transformations. Marcos is also a BCG Hender- son Institute Alumni Fellow, where he focused

on Systemic Trust. aguiar.marcos@bcg.com

Elif Seçgin is a principal at Boston Consulting Group, based in Istanbul. She focuses on the financial institutions and insurance sectors, creating innovative digital business models and leading transformational changes to meet industry needs. Elif is also a core member of BCG’s ESG in Emerging Markets team, based in Istanbul, where she helps clients integrate sustainability and ESG best practices across their operations.

Seckin Akar is a principal at Boston Consulting Group, based in Istanbul. He works closely with family conglomer- ates and is committed to advancing corporate governance and social impact.

Jeremy Hanson co-leads Heidrick & Struggles’ Global Sustainability Practice and is a member of the CEO & Board of Directors Practice. Jeremy is based

in the firm’s Chicago office. jhanson@heidrick.com

Marcos Macedo is a partner in the São Paulo office of Heidrick & Struggles and a member of the firm’s Industrial and Energy practices.

Sonia Tatar is executive director of the INSEAD Corporate Governance Centre and the INSEAD Wendel International Centre for Family Enterprise. She also serves on the boards of Chapter Zero France and the Nasdaq Centre for Board Excellence.

About BCG

Boston Consulting Group partners with leaders in business and society to tackle their most important challenges and capture their greatest opportunities. BCG was the pioneer in business strategy when it was founded in 1963. Today, we work closely with clients to embrace a transformational approach aimed at benefiting all stakeholders—empower- ing organizations to grow, build sustainable competitive advantage, and drive positive societal impact.

Our diverse, global teams bring deep industry and func- tional expertise and a range of perspectives that question the status quo and spark change. BCG delivers solutions through leading-edge management consulting, technology and design, and corporate and digital ventures. We work in a uniquely collaborative model across the firm and throughout all levels of the client organization, fueled by the goal of helping our clients thrive and enabling them to make the world a better place.

About BCG’s ESG in Emerging Markets

BCG’s ESG in Emerging Markets (EMs) initiative was created to drive impactful ESG efforts in emerging mar- kets. Our mission is to lead in ESG thought and action, build a strong community, and create offerings that ad- dress the specific needs of EM companies. Our approach combines diverse expertise, fosters partnerships, and aligns EM companies with the demands of a low-carbon, inclusive future.

About Heidrick & Struggles

Heidrick & Struggles is a premier provider of global leader- ship advisory and on-demand talent solutions, serving the senior-level talent and consulting needs of the world’s top organizations.

In our role as trusted leadership advisors, we partner with our clients to develop future-ready leaders and organiza- tions, bringing together our services and offerings in execu- tive search, diversity and inclusion, leadership assessment and development, organization and team acceleration, culture shaping, and on-demand, independent talent solutions. Heidrick & Struggles pioneered the profession of executive search more than 65 years ago. Today, the firm provides integrated talent and human capital solutions to help our clients change the world, one leadership team at a time.

About INSEAD, The Business School for the World

As one of the world’s leading and largest graduate busi- ness schools, INSEAD brings together people, cultures and ideas to develop responsible leaders who transform busi- ness and society. Our research, teaching and partnerships reflect this global perspective and cultural diversity.

With locations in Europe (France), Asia (Singapore), the Middle East (Abu Dhabi), and North America (San Francis- co), INSEAD’s business education and research spans four regions. Our 162 renowned Faculty members from 40 countries inspire more than 1,300 degree participants annually in our Master in Management, MBA, Global Executive MBA, Specialised Master’s degrees (Executive Master in Finance and Executive Master in Change) and PhD programmes. In addition, more than 10,000 execu- tives participate in INSEAD Executive Education pro- grammes each year.

INSEAD continues to conduct cutting-edge research and innovate across all our programmes. We provide business leaders with the knowledge and awareness to operate anywhere. Our core values drive academic excellence and serve the global community as The Business School for the World.

About INSEAD Corporate Governance Centre

The INSEAD Corporate Governance Centre (ICGC) is en- gaged in making a distinctive contribution to the knowl- edge and practice of corporate governance globally. Its vision is to be the leading center for research, innovation, and impact in the field. Through its educational portfolio and advocacy, the ICGC seeks to build greater trust within the public and stakeholder communities, so that business- es are a strong force for improvement, not only of econom- ic markets but also for the global societal environment.

The authors wish to thank those company directors who participated in the survey and roundtables for this report.

The authors additionally acknowledge those at BCG who supported the roundtables and the development of the publication. These include Nurlin Salleh, managing direc- tor and partner; Haikal Siregar, managing director and partner; Marc Schmidt, managing director and partner; and Katie Hill, partner and associate director.

Thanks are also extended to those at Heidrick & Struggles, including Hnn-Hui Hii, a partner in the Singapore office and co-lead of the CEO & Board of Directors Practice in Southeast Asia; Louise Huang, a principal in the Singapore office and a member of the Healthcare & Life Sciences Practice; Jiat-Hui Wu, the partner-in-charge of the Singa- pore office and co-lead of the CEO & Board of Directors Practice in Southeast Asia; Veronique Parkin, a partner in the Johannesburg office and a member of the CEO & Board Practice; and Josselyn Simpson, vice president, global editorial director.

The authors also acknowledge the contributions of Fabi- enne Chemin and Ivy Ng at the INSEAD Corporate Gover- nance Centre in developing the survey. They also thank BCG’s Natasha Peacock and Geoffrey Hoy and editor Jan Koch.